- Home

- Jean Plaidy

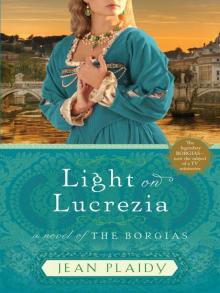

Light on Lucrezia: A Novel of the Borgias Page 4

Light on Lucrezia: A Novel of the Borgias Read online

Page 4

Cesare retired while the Cardinals discussed his case. There was not a man among them who did not regard the whole procedure as farcical. The Borgia Pope desired Cesare to be released from his vows; and who dared oppose the Borgia Pope?

Cesare went away with a light heart, knowing that before the week was out he would have achieved a lifelong ambition. He would be a soldier leading his armies, free of the restricting influence of the Church.

He came to his sister’s apartments where she was with her husband. Alfonso, the happy bridegroom, involuntarily moved closer to his wife as his brother-in-law came in.

“Ha!” cried Cesare. “The happy pair. Why sister, why brother, all Rome talks of your pleasure in each other. Do they speak truth?”

“I am very happy,” Lucrezia told him.

“We are happy in each other,” added Alfonso.

Cesare smiled his slow sardonic smile and as he looked at the handsome boy, a momentary anger possessed him. Such a boy! Scarce out of the nursery. Smooth-cheeked and pretty! Cesare’s once beautiful skin was marred now and would doubtless remain so for the rest of his life. It was strange that he, who felt that it would not be long before the whole of Italy was at his feet, should thus feel envy of the smooth cheeks of a pretty boy.

“Why,” he cried, “you do not seem pleased to see me!”

“We are always pleased to see you,” said Lucrezia quickly.

“Do not allow your wife to speak for you, brother,” put in Cesare, a faint sneer turning up the corners of his mouth. “You should be master, you know.”

“Nay,” said Alfonso, “it is not thus with us. I wish to please my wife, nothing more.”

“Devoted husband!” murmured Cesare. “Lucrezia, we are going to have days of celebration. Prepare yourself. What sort of fête shall I arrange for your pleasure?”

“There have been so many celebrations,” said Lucrezia. “Alfonso and I are happy enough without them. We have our hunting, our dancing and music.”

“And other pleasures in each other’s company I doubt not. Oh, but you are so newly wed. Nevertheless there shall be celebrations. Do you know, Lucrezia, that before long I discard my Cardinal’s robes?”

“Cesare!” She ran to him and threw herself into his arms. “But I am so happy. It is what you have wanted for so long. And at last it has come. Oh dearest brother, how I rejoice with you!”

“And you are ready to dance with me at a ball I shall give. You are ready to watch me kill a bull or two?”

“Oh Cesare … not that. It frightens me.”

He kissed her tenderly, and putting his arm about her he drew her to an embrasure; he stood looking at her, his back turned to Alfonso who, as Cesare intended he should, felt himself to be excluded.

Alfonso stood awkwardly, watching; and suddenly all his fears returned to him and he found he could not control his shivers. He could not take his eyes from them—the most discussed brother and sister in Italy, so graceful, both of them, with that faint resemblance between them, yet that vivid contrast. There was Cesare fierce and frightening, determined to dominate, and Lucrezia slender and clinging, wishing to be dominated. Seeing them thus, all Alfonso’s doubts and suspicions returned, and he wanted to beg Lucrezia to leave this place which now seemed to him evil. He wanted to rescue Lucrezia who, although she was born of them, was not one of them; he wanted to take her right away from her family and live in peace with her.

He heard their voices. “But you would not have me stand aside while others killed the bulls?”

“I would. Indeed I would.”

“But my dearest, you would then be ashamed of your brother.”

“I should never be ashamed of you. And you risk your life with the bulls.”

“Not I. I’m a match for any bull.”

Cesare turned and drew her to him and over her head smiled for a second of triumphant mockery at Alfonso. Then he released her suddenly and cried: “But we have forgotten your little bridegroom, Lucrezia. I declare he looks as though he is about to burst into tears.”

Alfonso felt the blood rush to his face. He started forward but Cesare stood between Lucrezia and her husband, legs apart, his hand playing with the hilt of his sword; and although Alfonso wanted to draw his own sword and challenge this man here and now to fight, and fight to the death if need be, he felt as though his limbs would not move, that he was in the presence of the devil, who had laid a spell upon him.

Cesare laughed and went out; and when he was no longer there Alfonso’s courage came back to him. He went to Lucrezia and took her by the shoulders. “I like not his manners,” he said. Lucrezia’s eyes were wide and innocent. “He … he is too possessive. It is almost as though …” But he could not say it. He had not the courage. There were questions he wanted to ask, and he was afraid to ask them. He had been so happy, and he wanted to go on being happy.

Lucrezia put her arms about his neck and kissed him in that gentle way which never failed to be a source of excitement to him.

“He is my brother,” she said simply. “We were brought up together. We have shared our lives and it has made us good friends.”

“It would seem when he is by that you are unaware of any other.”

She laid her head against his chest and laughed. “You are indeed a jealous husband.”

“Lucrezia,” he cried, “have I cause to be?”

Then she lifted her face to his and her eyes were still full of limpid innocence. “You know I want no other husband,” she said. “I was unhappy, desperately unhappy, and I thought never to laugh in joy again. Then you came, and since you came, I have found happiness.”

He kissed her with increasing passion. “Love me, Lucrezia,” he pleaded. “Love me … only.”

They clung together, but even in the throes of lovemaking Alfonso could not rid himself of the memory of Cesare.

Cesare was in the ring. The assembled company watched him with admiration, for he was the most able matador in Rome. His Spanish origin was obvious as, lithe and graceful, he twisted his elegant body this way and that, springing from the path of the onrushing bull at that precise moment in time when death seemed inevitable.

Alfonso, sitting beside Lucrezia and watching her fingers twisting the embroideries on her dress, was aware of the anxiety she was experiencing. Alfonso did not understand. He could have sworn that she was glad because Cesare would soon be leaving for France; yet now, watching his antics in the bullring, he was equally sure that she was conscious of no one but her brother.

Alfonso murmured: “God in Heaven, Holy Mother and all the saints, let him not escape. Let the furious bull be the instrument of justice—for many have died more horribly at his hands.”

Smiling coolly Sanchia watched the man who had been her lover. She thought: I hope the bull gets him, tramples him beneath those angry hoofs … not to kill him … no, but to maim him so that he will never walk or run or leap again, never make love to his Carlotta of Naples. Carlotta of Naples! Much chance he has! But let him lose his beauty, and his manhood be spoiled, so that I may go to him and laugh in his face and taunt him as he has taunted me.

Among those who watched there were others who remembered suffering caused them by Cesare Borgia, many who prayed for his death.

But had Cesare died that day there would have been three to mourn him with sincerity—the Pope who watched him with the same mingling of pride and fear as Lucrezia’s; Lucrezia herself; and a red-headed courtesan named Fiametta, who had sought to grow rich by his favors and found that she loved him.

But, for all the wishes among the spectators in the ring that day, Cesare emerged triumphant. He slew his bulls. He stood the personification of elegance, indolently accepting the applause of the crowds. And he seemed a symbol of the future, there with his triumph upon him. His proud gestures seemed to imply that the conqueror of bulls would be the conqueror of Italy.

The Pope sent for his son that he might impart the joyful news.

“Louis promises not to b

e ungenerous, Cesare,” he cried. “See what he offers you! It is the Dukedom of Valence, and a worthy income with the title.”

“Valence,” said Cesare, trying to hide his joy. “I know that to be a city on the Rhône near Lyons in Dauphiné. The income … what is that?”

“Ten thousand écus a year,” chuckled the Pope. “A goodly sum.”

“A goodly sum indeed. And Carlotta?”

“You will go to the French Court and begin your wooing at once.” The Pope’s expression darkened. “I shall miss you, my son. I like not to have the family scattered.”

“You have your new son, Father.”

“Alfonso!” The Pope’s lips curled with contempt.

“It would seem,” muttered Cesare, “that the only member of the family who is pleased with its new addition is Lucrezia.”

The Pope murmured indulgently: “Lucrezia is a woman, and Alfonso a very handsome young man.”

“It sickens me to see them together.”

The Pope laid his hand on his son’s shoulder. “Go to France, my son. Bring back the Princess Carlotta as soon as you can.”

“I will do so, Father. And when Carlotta is mine I shall stake my claim to the throne of Naples. Father, no one shall prevent my taking that to which I have a claim.”

The Pope nodded sagely.

“And,” went on Cesare, “if I am heir to the crown of Naples, of what use to us will Lucrezia’s little husband be?”

“That is looking some way ahead,” said Alexander. “I came through my difficulties in the past because I did not attempt to surmount them until they were close upon me.”

“When the time comes we shall know how to deal with Alfonso, Father.”

“Indeed we shall. Have we not always known how to deal with obstacles? Now, my son, our immediate concern is your own marriage, and I shall not wish you to appear before the King of France as a beggar.”

“I shall need money to equip me.”

“Fear not. We’ll find it.”

“From the Spanish Jews?”

“Why not? Should they not pay for the shelter I have given them from the Spanish Inquisition?”

“They will pay … gladly,” said Cesare.

“Now my son, let us think of your needs … your immediate needs.”

They planned together, and the Pope was sad because he must soon say good-bye to his beloved son, and he was fearful too because he had once vowed that Cesare should remain in the Church, and now Cesare had freed himself. Alexander felt suddenly the weight of his years, and in that moment he knew that that strong will of his, which had carried him to triumph through many turbulent years, was becoming more and more subservient to that of his son Cesare.

The days of preparation were over. The goldsmiths and silversmiths had been working day and night on all the treasures which the Duke of Valence would take with him into France. The shops of Rome were denuded of all fine silks, brocades, and velvets, for nothing, declared the Pope, was too fine for his son Cesare; the horses’ shoes must be of silver, and the harness of the mules must be fashioned in gold; Cesare’s garments must be finer than anything he would encounter in France, and the most magnificent of the family jewels must be fashioned into rings, brooches and necklaces for Cesare. Nothing he used—even the most intimate article of toilet—must be of anything less precious than silver. He was going to France as the guest of a King, and he must go as a Prince.

He left Rome in the sunshine of an October day, looking indeed princely in his black velvet cloak (cut after the French fashion) and plumed hat. Beneath the cloak could be seen his white satin doublet, gold-slashed, and the jewels which glittered on his person were dazzling. Because he hated any to remember that he was an ex-Cardinal he had covered his tonsure with a curling wig which gave him an appearance of youth; for those who watched in the streets could not see the unpleasant blemishes, the result of the male francese, on his skin.

He was no longer Cardinal of Valencia, but Duke of Valentinois and the Italians called him Il Valentino.

The Pope stood on his balcony with Lucrezia beside him, and as the calvacade moved away and on to the Via Lata, the two watchers clasped hands and tears began to fall down their cheeks.

“Do not grieve. He will soon be with us once more, my little one,” murmured Alexander.

“I trust so, Father,” answered Lucrezia.

“Bringing his bride with him.”

Alexander had always been optimistic, and now he refused to believe that Cesare could fail. What if the King of Naples had declared his daughter should never go to a Borgia; what if it were impossible to trust sly Louis; what if all the Kings of Europe were ready to protest at the idea of a bastard Borgia’s marrying a royal Princess? Cesare would still do it, the Pope told himself; for on that day, as he watched the glittering figure ride away, in his eyes Cesare was the reincarnation of himself, Roderigo Borgia, as he had been more than forty years earlier.

With the departure of Cesare a peace settled on the Palace of Santa Maria in Portico, and the young married pair gave themselves up to pleasure. Alfonso forgot his fears of the Borgias; it was impossible to entertain them when the Pope was so affectionate and charming, and Lucrezia was the most loving wife in the world.

All commented on the gaiety of Lucrezia. She hunted almost every day in the company of Alfonso; she planned dances and banquets for the pleasure of her husband, and the Pope was a frequent participator in the fun. It seemed incredible to Alfonso that he could have been afraid. The Pope was so clearly a beloved father who could have nothing but the warmest feelings toward one who brought such happiness to his daughter.

Lucrezia was emerging as the leader of fashion; not only were women wearing golden wigs in imitation of her wonderful hair, they were carefully studying the clothes she wore and copying them. Lucrezia was childishly delighted, spending hours with the merchants, choosing materials, explaining to her dressmakers how these should be used, appearing among them in the greens, light blues and golds, in russet and black, all those shades which accentuated her pale coloring and enhanced her feminine daintiness.

Lucrezia felt recklessly gay. This was partly due to the discovery that, contrary to her belief, she could be happy again. Whole days passed without her thinking of Pedro Caldes, and even when she did so it was to assure herself that their love had been a passing fancy which could never have endured in the face of so much opposition. Her father was right—as always. She must marry a man of noble birth; and surely she was the happiest woman on Earth, because Alfonso was both noble and the husband she loved.

The household heard her laughing and singing, and they smiled among themselves. It was pleasant to live in the household of Madonna Lucrezia; it was comforting to know that she had given up all thought of going into a convent. A convent! That was surely not the place for one as gay and lovely, as capable of being happy and giving happiness, as Lucrezia.

They knew in their hearts that the peace of the household was due to the absence of one person, but none mentioned this. Who could doubt that an idle word spoken now might be remembered years hence? And Il Valentino would not remain forever abroad.

The days passed all too quickly, and when in December Lucrezia knew that she was going to have a baby, she felt that her joy was complete.

Alfonso was ridiculously careful of her. She must rest, he declared. She must not forget the precious burden she carried.

“It is soon yet to think of that, my dearest,” she told him.

“It is never too soon to guard one’s greatest treasures.”

She would lie on their bed, he beside her, while they talked of the child. They would ponder on the sex of the child. If it were a boy they would be the proudest parents on Earth; and if a girl, no less proud. But they hoped for a boy.

“Of course we shall have a boy,” Alfonso declared, kissing her tenderly. “How, in this most perfect marriage could we have anything else? But if she is a girl, and resembles her mother, then I think we shall be equ

ally happy. I see nothing for us but a blissful life together.”

Then they loved and told each other of their many perfections and how the greatest happiness they had ever known came from each other.

“One day,” said Alfonso, “I shall take you to Naples. How will you like living away from Rome?”

“You will be there,” Lucrezia told him, “and there will be my home. Yet …”

He touched her cheek tenderly. “You will not wish to be long separated from your father,” he said.

“We shall visit him often, and perhaps he will visit us.”

“How dearly you love him! There are times when I think you love him beyond all others.”

Lucrezia answered: “It is you, my husband, whom I love beyond all others. Yet I love my father in a different way. Perhaps as one loves God. He has always been there, wise and kind. Oh Alfonso, I cannot tell you of the hundred kindnesses I have received at his hand. I do not love him as I love you … you are part of me … I am completely at ease with you. You are my perfect lover. But he … is the Holy Father of us all, and my own tender father. Do not compare my love for him with that I have for you. Let me be happy, in both my loves.”

Alfonso was reminded suddenly of the loud sardonic laughter of Cesare, and he had an uncanny feeling that the spirit of Cesare would haunt him all his life, mocking him in his happiest moments, besmirching the brightness of his love.

But he did not mention Cesare.

He, like Lucrezia, often had the feeling that they must hold off the future. They must revel in the perfect happiness of the present. It would be folly to think of what might come, when what was actually happening gave them so much pleasure. Did one think of snowstorms when one picnicked on warm summer evenings in the vineyards about the Colosseum? One did not spoil those perfect evenings by saying: “It will be less pleasant here two months hence.”

A Health Unto His Majesty

A Health Unto His Majesty Courting Her Highness

Courting Her Highness The Queen's Husband

The Queen's Husband To Hold the Crown: The Story of King Henry VII and Elizabeth of York

To Hold the Crown: The Story of King Henry VII and Elizabeth of York Queen in Waiting: (Georgian Series)

Queen in Waiting: (Georgian Series) Daughter of Satan

Daughter of Satan The Follies of the King

The Follies of the King The Revolt of the Eaglets

The Revolt of the Eaglets The Hammer of the Scots

The Hammer of the Scots In the Shadow of the Crown

In the Shadow of the Crown Goddess of the Green Room: (Georgian Series)

Goddess of the Green Room: (Georgian Series) Caroline the Queen

Caroline the Queen The Rose Without a Thorn

The Rose Without a Thorn Victoria in the Wings: (Georgian Series)

Victoria in the Wings: (Georgian Series) The Italian Woman

The Italian Woman The Bastard King

The Bastard King Queen of This Realm

Queen of This Realm The Road to Compiegne

The Road to Compiegne The Merry Monarch's Wife

The Merry Monarch's Wife The Captive Queen of Scots

The Captive Queen of Scots Light on Lucrezia: A Novel of the Borgias

Light on Lucrezia: A Novel of the Borgias The Third George: (Georgian Series)

The Third George: (Georgian Series) Passage to Pontefract

Passage to Pontefract The Three Crowns epub

The Three Crowns epub The Red Rose of Anjou

The Red Rose of Anjou The Passionate Enemies

The Passionate Enemies The Third George

The Third George The Murder in the Tower: The Story of Frances, Countess of Essex

The Murder in the Tower: The Story of Frances, Countess of Essex The Princess of Celle: (Georgian Series)

The Princess of Celle: (Georgian Series) Royal Sisters: The Story of the Daughters of James II

Royal Sisters: The Story of the Daughters of James II Katharine of Aragon

Katharine of Aragon Beyond the Blue Mountains

Beyond the Blue Mountains Perdita's Prince: (Georgian Series)

Perdita's Prince: (Georgian Series) The Queen from Provence

The Queen from Provence The Widow of Windsor

The Widow of Windsor The Shadow of the Pomegranate

The Shadow of the Pomegranate The Battle of the Queens

The Battle of the Queens Madame Serpent

Madame Serpent The Lion of Justice

The Lion of Justice The King's Confidante: The Story of the Daughter of Sir Thomas More

The King's Confidante: The Story of the Daughter of Sir Thomas More The Wondering Prince

The Wondering Prince Plantagenet 1 - The Plantagenet Prelude

Plantagenet 1 - The Plantagenet Prelude The Star of Lancaster

The Star of Lancaster Louis the Well-Beloved

Louis the Well-Beloved A Favorite of the Queen: The Story of Lord Robert Dudley and Elizabeth 1

A Favorite of the Queen: The Story of Lord Robert Dudley and Elizabeth 1 The Queen's Secret

The Queen's Secret The Courts of Love: The Story of Eleanor of Aquitaine

The Courts of Love: The Story of Eleanor of Aquitaine The Vow on the Heron

The Vow on the Heron Flaunting, Extravagant Queen

Flaunting, Extravagant Queen Loyal in Love: Henrietta Maria, Queen of Charles I

Loyal in Love: Henrietta Maria, Queen of Charles I Mary, Queen of France: The Story of the Youngest Sister of Henry VIII

Mary, Queen of France: The Story of the Youngest Sister of Henry VIII For a Queen's Love: The Stories of the Royal Wives of Philip II

For a Queen's Love: The Stories of the Royal Wives of Philip II Victoria Victorious: The Story of Queen Victoria

Victoria Victorious: The Story of Queen Victoria The Heart of the Lion

The Heart of the Lion Madonna of the Seven Hills: A Novel of the Borgias

Madonna of the Seven Hills: A Novel of the Borgias The Queen's Favourites aka Courting Her Highness (v5)

The Queen's Favourites aka Courting Her Highness (v5) The King's Secret Matter

The King's Secret Matter The Sixth Wife: The Story of Katherine Parr

The Sixth Wife: The Story of Katherine Parr The Lady in the Tower

The Lady in the Tower The Complete Tudors: Nine Historical Novels

The Complete Tudors: Nine Historical Novels Queen Jezebel

Queen Jezebel The Thistle and the Rose

The Thistle and the Rose Castile for Isabella

Castile for Isabella Royal Road to Fotheringhay

Royal Road to Fotheringhay Murder Most Royal: The Story of Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard

Murder Most Royal: The Story of Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard Sweet Lass of Richmond Hill: (Georgian Series)

Sweet Lass of Richmond Hill: (Georgian Series)